It’s not X, it’s Y, is a particular English construct that has drawn more than the usual amount of discussion in recent months.

Language used to be for storytelling. You might begin your work with one theme, one event; as it progressed, you could explore some aspect of that world, painting a picture as you went.

Your attention, and the readers’, would be directed, focused, then drawn elsewhere, in some curated trajectory. Some paragraphs would keep you on your toes; some sentences left you space to breathe, to integrate the latest shocking sequence of events. In a writing course, this might be called pacing, or perhaps flow.

But now — year two thousand and twenty five — most people get their reading from the internet. E-books, YouTube videos, TikTok shorts, tweets, skeets, Google Meets, Temu DMs, Microsoft Teams messages, VRChat parties, text messages, conspiratorial Minecraft conversations, Slack blasts. One may be shocked to find that there is little writing (one might go as far as to say no language at all) that doesn’t pass through the internet.

And what does the internet run on, these days? Search engines. Links; digestibility. Easy context, uniformity to random sampling: searchability. Everything must be SEO-optimized; everything must be accessible to the least intelligent vector database and the most intelligent CEO-driven LLM.

In time, given these evolutionary pressures, the fittest on the Internet have invented a new lingua franca. GPT English.

You probably know by heart some of the earlier features of GPT English: overuse of “delve,” random insertion of the phrase, “As a language model, I cannot [XYZ],” constant use of em-dash, and of course, perfect spelling and punctuation juxtaposed with grammar as eye-catching as gravel. Naturally, there’s also, “it’s not x, but y,” but we’ll get to that.

It turns out that to fool the gatekeepers of the Internet, technology companies, into promoting your content, to make it appear to be high quality, you merely need to fool the robotic draughthorses (LLMs) of their minions (employees). And you can always use their newest publicly released weapons against them.

You can take your writing to GPT, however mediocre and forgettable, and ask it for improvements. It can just be an outline: a mere sketch of a few concepts you want to write about. You can feed it into the LM, smash ten or twenty keys to incoherently specify what you want, and lie back as it chugs out tokens like puffs of exhaust from a two-stroke leafblower engine. Oh, you made a typo in your request? It didn’t even notice.

What actually goes on in there? Nobody knows, exactly. But whatever the reason, it has the tendency, lacking any specific life experience or fixed frame of mind, to stretch your words and contort them in the absence of additional details. You might have written,

“The sky was blue.”

It can’t really improve on that, but it can say the opposite; it’s great at coming up with opposites for basic concepts. [2] So it “upgrades” your sentence. It writes,

“The sky — it was not blue in the way oceans are blue, or eyes in bad poetry are blue — but blue in the way silence is loud, in the way a lie is too perfect, in the way something knows it’s being watched and performs anyway.” [1]

There’s nothing technical there. Oh, maybe there’s some artistic talent there, if you’re the kind of writer who likes to take artistic credit for the product of a language model. If not, then in terms of structure, or coherence of overall narrative, or any artistic intent to evoke something, it has added nothing.

“It’s not X, but Y” is the latest fake bones injected into a piece of writing in place of actual structure. It is constructing a “chicken leg” by wrapping burger meat and a leather wallet around a Ticonderoga pencil.

It’s disruptive, and yes, it’s surprising, forcing the reader to predict the latest misdirection. Some people have proposed this is actually critical to the way LLMs think, processing tokens one by one. [3] They theorize that having junctures where a single token matters helps sharply spike the learning rate — like how we imprint on the final digit of the equation “2+2=4.” There’s only one possible correct outcome.

Maybe it’s more efficient for a backpropagation-driven LLM, but after the thousandth time reading that specific construction in a week, some people find it grating. It’s sand in their eyes. People hate repetition!

What’s a good analog for this?

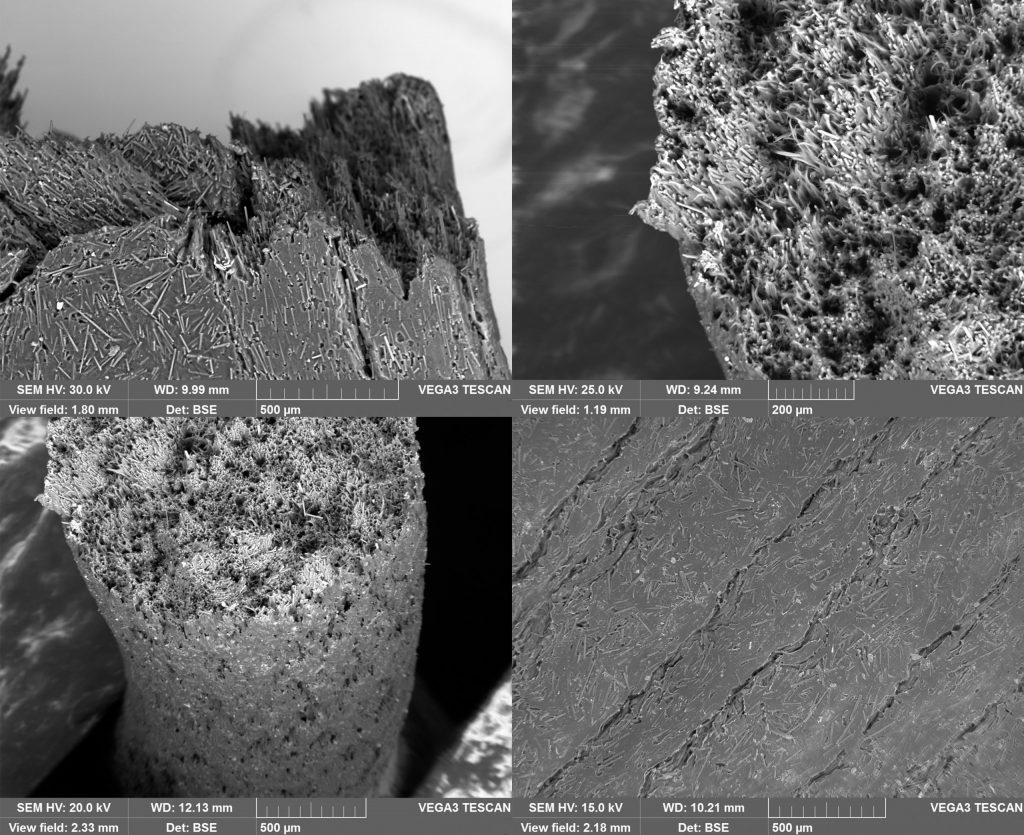

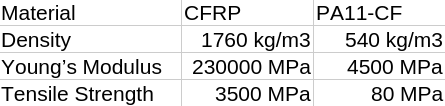

Some high-performance mechanical components are composites built with vacuum molding. You design a mold for a curved part, then lay aligned sheets of woven fabric into it and infuse them with an epoxy binder. Draw a vacuum and let it cure: your part is done.

But GPT digested language, GPT-ed structure, is more like 3D-printing whatever you’re trying to make from a slurry of nylon filled with tenth-of-a-millimeter fragments of the same fiber.

It sure is a lot easier to print when you don’t have to align any fibers — when they all flow, slickly and automatically, from a hardened alloy nozzle.

But is it really the same? Is it remotely as compelling, as strong?

GPT English is everywhere now. It’s in advertisements, it’s in marketing, it’s in tweets, it’s in scripts for YouTube videos. Maybe it’s even something you’ve written. It’s up to you whether to leave it in or not.

[1] Written by GPT-5 when asked to behave like GPT-4.

[2] We gave language models these abilities by design. We let them operate, not on words, but on word embeddings [2.1], which effectively map separable concepts and words onto easily interpretable sliders in a high-dimensional space.

For an LLM, computing that “king + female” equals “queen” in embedding space is no more difficult than counting to two is for a person with fingers.